Patellar (“Knee Cap”) Luxation (Dislocation)

What is a Patella?

What is a Patella?

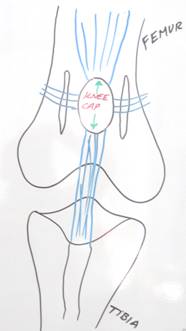

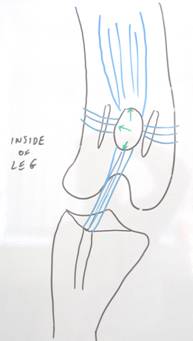

The patella is a bone within the tendon of the thigh muscle (quadriceps). A bone that develops within a tendon is called a sesamoid bone and its purpose is to protect the tendon from wear and tear as the tendon passes over another bone. If the patella did not exist then the tendon would rub on the end of the femur (thigh bone). As the thigh muscle contracts it pulls the patella up the groove in the end of the femur as the knee (stifle) is extended. When the thigh muscle relaxes and the hamstrings muscles contract the knee become flexed and the patella is pulled back down that groove. There are also ligaments from each side of the patella running around to the back of the knee to help to stop it being pulled sideways as a dog twists and turns on the leg.

Why does a Patella Luxate / Dislocate?

On rare occasions the patella dislocates as a result of some form of injury involving a blow to the side of the front of the knee. Such dislocations are fairly easy to treat as repair of the torn tissue will generally lead to a rapid and complete recovery.

®

®

In most dogs with patellar luxation the cause relates to fairly subtle deformities through the length of the leg that mean the patella does not line up properly with the groove at the end of the thigh bone (femur). The nature of the deformity varies between patients but in general involves a mild bowing at the end of the thigh bone and/or a bowing/twisting of the top end of the shin bone (tibia). This means as the thigh muscle contracts the patella wants to go into the straight line between the top of the muscle and the point where the tendon attaches to the tibia (like a bead on a string that is pulled tight). The direction in which the bones are bowed will affect which way the patella tries to dislocate. In the drawings above the patella is shown dislocating towards the inside of the leg, which is the most common direction for it to go, by far. Patellar luxation is far more common in the smaller breeds but still occurs quite regularly in the larger breeds also. If the problem develops in one knee then it might well be found in the other leg, either at the same time or soon afterwards – but not always.

What signs will a Dog show if they have a Luxating Patella?

First of all it is important to realise that NOT ALL dogs with a dislocating patella actually show any signs at all. Many dogs, particularly those of the smaller breeds, will lead full and active lives with one or both of their patellae showing a tendency to dislocate on clinical examination.

The classical (“text book”) signs described are that a dog will suddenly pick the leg up when walking or running, hop for a few strides then start to put the leg down again, returning to normal very quickly. This pattern can then repeat with varying frequency. If the patella becomes permanently dislocated then the lameness tends to be seen all the time and, at worst they might hold the leg up for most or all of the time. If both legs are affected then they might appear very crouched as they walk because they cannot straighten either of their knees properly.

A diagnosis by a Veterinary Surgeon is made from the history and finding that the patella in that leg can be made to dislocate when manipulating the leg. X-rays are then used to add information about the nature of the deformity causing the problem. In some cases the patella will be dislocated on the X-ray but in those where it only happens intermittently the patella is likely to be in its normal position. The X-rays are also used to check for other possible explanation for the lameness because, as was pointed out in the paragraph above, dislocation of the patella does not always cause lameness. In addition, there might also be complicating factors (particularly where the diagnosis is being made in adults) as outlined in the next section below.

X-ray of a Toy Poodle’s knee (stifle) lowing from in front of the leg. The knee cap is displaced well over to the inside of the joint (arrow) when it should lie on top of the end of the femur (thigh bone).

X-ray of a Toy Poodle’s knee (stifle) lowing from in front of the leg. The knee cap is displaced well over to the inside of the joint (arrow) when it should lie on top of the end of the femur (thigh bone).

What happens if the problem is left Untreated?

The first point to make is that patellar luxation does not need treating if it is not causing a problem. If the dog is fully active with no evidence of lameness and the problem has only been picked up on a routine physical examination then there is no justification for any treatment.

However, if the patellar luxation is thought to be causing lameness then surgical treatment is to be recommended. There is no value for waiting for a dog to “grow up” because the severity of the luxation, and so the difficulty returning the patella to its normal position, tends to become worse with time. Hence it is best to treat the problem as soon (within reason) as it is recognised as a problem – though it is not an “emergency” as such.

In dogs that develop lameness as adults patellar luxation may be the cause as a result of it having taken time for the ligaments mentioned earlier to stretch and allow the patella to dislocate from the groove on the end of the thigh bone. However, the cause of the lameness might be another problem affecting the knee (e.g. failure of the cruciate ligament – see details of this condition elsewhere on the site) with the patellar being a complicating issue. Generally, it will be necessary to treat the patellar luxation as well as what ever else has developed in order to regain good function in the leg.

What can we do to help – Surgery?

It has been well accepted, over many years, that surgical correction of the alignment of the patella, so that it runs through the groove at the end of the thigh bone, generally gives good results. Success rates will vary as a result of many factors, including:

- Surgeon experience

- Technique used

- Patient (and Owner) co-operation with aftercare

Please note that the success rates outlined below are based on our continual monitoring of outcomes for patients treated at Weighbridge Referral Centre by Steve Butterworth, who has undertaken treatment of a few hundred patients with this problem over more than 15 years.

In a few cases it might be possible to stop the patella from dislocating by tightening up the ligament on the opposite side of the knee. In some cases the groove that the patella should sit in has become shallow and needs to be made deeper. Using one or both of these techniques is generally only successful in young dogs (less than 5 months or so) where they might then grow “correctly” once the patella has been restored to its normal position. However, in severe cases where the patella is permanently dislocated or the dog is reaching / has reached maturity and is not growing anymore, these techniques will often fail – with the patella starting to dislocate again within a few weeks or months of treatment.

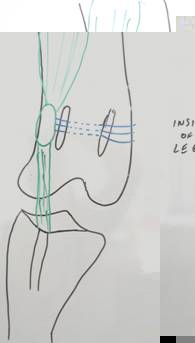

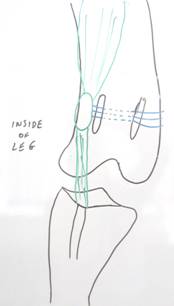

In most cases it is necessary to realign the patella with the knee by changing the shape of one of the bones (femur or tibia). In addition to this it is often necessary to deepen the groove in which the patellar should sit and also to tighten up the ligament that has become stretched. There are two main ways of re-aligning the patella.

Tibial Crest Transposition (TCT)

This technique has been used for a long time, is the simplest method of re-aligning the patella with the groove at the end of the femur (thigh bone) and gives good results in most cases. It involves cutting the part of the tibia (shin bone) to which the patellar tendon attaches. The bone is left attached at the bottom end and is swung across, taking the tendon with it, until the point of tendon attachment lines up with the muscle running down the thigh and the groove in the femur. Once in its new position the tibial crest is held there by driving a small pin through it and into the main body of the tibia.

(Distal) Femoral Wedge Osteotomy (DFWO)

This technique has been developed as a result of poor results of TCT in some dogs, particularly in the larger breeds and where the deformity is severe making it difficult to move the tibial crest far enough to achieve its goal. In such cases it is often the bowing at the end of the femur that is the main reason for the patella dislocating. Correction of the problem is aimed at straightening the end of the femur by removing a wedge of bone from it, closing the gap and securing the two pieces of bone together with a bone plate (that has been specially designed for the purpose). In some cases it proves necessary to combine this technique with a TCT as well.

Aftercare (for both procedures)

The process of bone healing takes 6-12 weeks (depending on the age of patient and the type of surgery involved) and it is important that during that time the dog is restricted in his / her activities. They are allowed as much lead exercise (on a short leash) as they can tolerate – increasing the duration of walks as they recover. But they are not allowed freedom around the house or the garden, with no access to furniture or free access to stairs (can be walked up and down these if required, but not allowed to run up and down them at will). When not on the end of a lead they should be restricted to a pen or small room containing no furniture and with a non-slip floor. Once this period has passed, and preferably an X-ray (in the case of DFWO) has shown bone healing is complete, it is usually possible to steadily increase activity levels, with re-introduction of off lead exercise, over the next month or two.

The metal implants used to stabilise the bone can generally stay in place but occasionally they cause irritation, resulting in lameness or biting at the knee, in which case their removal is advisable.

So what results can be expected with surgery?

If there are no complications and the post-operative plan is kept to by the patient and their owners then the results are fairly consistent. Although they are NOT influenced by the size of patient the larger dogs tend take longer to reach their best. Satisfactory results are seen in over 90% of cases. Young dogs are more likely to regain completely normal use of the leg because the tissues are stiffer in older dogs and their joints have often suffered more “wear and tear”, meaning that they are more likely to show stiffness after rest or mild / intermittent lameness at exercise compared with their younger counterparts, even though their patella no longer dislocates.