Elbow Dysplasia

What is Elbow Dysplasia?

Elbow dysplasia is a very general term that relates to a number of conditions involving the elbow joint. The basic link between these conditions is that they are a result of the elbow joint not forming or developing correctly. The 3 main conditions that are recognised under the “umbrella” term of elbow dysplasia are:

- Coronoid Process disease / fragmentation (FCP)

- Ununited Anconeal Process (UAP)

- Osteochondritis Dissecans (OCD) of the elbow

Other conditions may fall into this group but are not yet universally accepted as such. OCD in the elbow tends to affect one particular part of the humerus and this is discussed elsewhere (see “OCD”). The discussion below will focus on the forms of elbow dysplasia that are thought to be primarily associated with joint incongruency.

The joint surface of the elbow is made up of three bones (the humerus, the radius and the ulna), which makes it fairly unique in the dog’s skeleton. It is also a fairly tight-fitting hinge joint, which means it is far less tolerant of any incongruency (poor fitting) compared with other joints such as the shoulder or hip. The cause of the elbow becoming dysplastic is multifactorial and incompletely understood. Genetics play a role and there is a scoring scheme being used to try and reduce its prevalence by selective breeding. However, other (unknown) factors also play a large role and so the breeding programmes will only help the situation to a limited extent. The ways in which the joint can become incongruent is also very complex and the explanation below must be seen as a VERY simplified version of the real events.

If we consider the radius and ulna it can be seen that if they fail to grow at the same rate during a puppies development then a “step” will develop in the elbow joint. Normally about 70% of the load travelling down the humerus is transferred directly to the radius and about 30% to the ulna. If the radius becomes relatively short compared with the ulna then load bearing through the joint surface will change such that when the foot strikes the ground, 100% of the load will go on to the ulna and, in particular, the coronoid process (which is the part of the ulna that borders on to the radius). The step is generally very small and the gap between the humerus and the radius will close down and weight be transferred over to the radius. But every time the foot strikes the ground the coronoid process will, momentarily, be overloaded. Also the effect of the humerus “rocking” over onto the radius will cause a repetitive sprain type injury in the ligaments supporting the joint. Overloading of the coronoid process will cause damage within its structure (mini-fractures that heal but keep recurring) and this damage might appear as fissures in the cartilage on its surface, or fragments might become separated off – fragmented coronoid process (FCP).

On the other hand, what if the radius becomes relatively longer than the ulna. Then the radial head pushes the humerus “backwards” on the ulna. This means the humerus will be pushed up against the anconeal process. This process starts off life as a separate bone to the ulna and fuses with it by about 5 months of age. Up until then the two bones (anconeal process and ulna) are separated by a plate of cartilage – seen as a gap along the base of the process on X-rays. If the radius pushes the

humerus against the anconeal process then as the elbow flexes and extends the process is rocked as it rubs against the humerus. This not only damages the joint surface where they rub together but can also cause the anconeal process not to fuse to the ulna – ununited anconeal process (UAP).

It must be reiterated that this explanation of how FCP and UAP develop is very simplified and it is fairly easy to “pick holes” in it. However, it does help to give some idea of what is going on!

Whatever form of elbow dysplasia is present it will cause a secondary osteoarthritis, which will often contribute to the signs seen in the short or long term (see below).

Elbow dysplasia is seen mainly in medium and large breeds of dog and the type of problem seen also tends to show breed predispositions (e.g. Labradors and Rottweilers tend to show FCP, whilst German Shepherd Dogs and Irish Wolf Hounds tend to show UAP).

What Signs will a Dog with Elbow Dysplasia Show?

It is important to be aware that not ALL dogs with elbow dysplasia will show clinical signs and, in particular, may not show signs in both forelimbs despite the problem being bilateral (as judged from X-rays). If they do show signs then these will relate to lameness. If the signs are restricted to only one forelimb then the most obvious feature is the dog showing a nodding of the head as they walk or a tendency to lift or rest the paw when sitting (so as to keep weight off the limb). The nodding is a way of keeping the weight of their head on their good leg so it is the leg that is taking weight when the head is UP that is the bad leg. If the signs are present in both forelimbs then lameness might not be so dramatic because both legs hurt equally. As a result the signs relate more to showing a shuffling gait, reluctance to jump down or come down stairs, or simply a reduced willingness to exercise. Whether one or both forelimbs are affected, another sign that may be seen is stiffness after rest following exercise. This sign is often related to arthritis that develops as a consequence of the irritation caused to the joint by the dysplasia.

In most cases where the elbow dysplasia itself is the cause of the lameness it will be seen in young dogs less than a year of age, whereas when lameness is seen in adult dogs it is a result of the secondary arthritis. However, this is not always the case and the primary elbow dysplasia can start to cause lameness in dogs of upto 3 or 4 years of age.

How is Elbow Dysplasia Diagnosed?

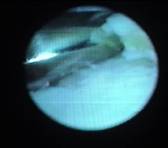

X-ray showing changes around Arthroscopy showing large X-ray showing UAP – line

Coronoid Process fragments of Coronoid visible across base of AP

Your Veterinary Surgeon will probably have a strong suspicion that this is the problem in a dog of the “right” breed and age showing lameness associated with elbow joint pain. Confirmation can usually be gained from X-rays that will show changes indicative of elbow dysplasia AND no other explanation for the elbow pain. The changes seen on X-rays take time to develop and so there may be no changes in some patients that have only just started showing lameness. However, this is not always the case because the joint disease can be in progress for a while before any lameness is seen. If no changes are see in X-rays to help confirm the diagnosis then the options are either to wait and take more X-rays after a few weeks or else to proceed with arthroscopy (“key hole camera”) to look directly at the joint surface and see if any damage is evident. Which of these two options is chosen will often depend on the severity of the signs.

How can Elbow Dysplasia be Treated?

Conservative Management

In some cases showing signs of elbow dysplasia the signs will improve over a 4-6 week period of nothing more than controlled exercise +/- painkillers (if required). This may be a result of the joint incongruency resolving as they continue to grow or the joint surface remodelling so that it forms a “better fit”. Although some patients might take longer than this to improve it is generally accepted that if they are not significantly better after a 4-6 week period then surgical treatment should be considered.

Surgery

What exactly this will involve depends on the type of elbow dysplasia present, i.e. whether the problem relates to disease of the Coronoid Process (FCP) or Anconeal Process (UAP).

FCP

In cases that fail to improve with the conservative management outlined above, surgery to remove the damaged portion of the coronoid process will significantly improve 65-75% of them. Such surgery can be carried out using an arthrotomy (where the joint is opened up completely) or else by arthroscopy (“key hole surgery”) using a “magic eye” camera. In recent years it has become accepted that although arthroscopic surgery might not lead to a higher rate of success in resolving lameness, it does allow a more rapid recovery and, if necessary, both elbows can be operated on under one anaesthetic.

In cases that fail to respond to such surgery there are more complex techniques that aim to improve the joint congruency (how well it fits together) and these can be considered when necessary.

UAP

In cases that fail to improve with the conservative management outlined above, surgery can resolve the lameness in the majority of cases. When the AP has failed to fuse to the ulna but has not completely separated from it, a surgical technique that involves cutting the ulna just below the elbow joint is often used. This allows the ulna to move and align itself better with the radius. Although the lameness will be worse to begin with because the bone has been broken and left without internal support, once the bone has healed the lameness usually resolves completely. Some surgeons consider it is necessary to fix the AP on to the ulna using a bone screw as well as cutting the ulna. So far there is no evidence that this improves the clinical outcome and so at Weighbridge Referral Centre the treatment usually involves only cutting the ulna.

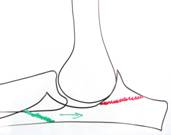

Green line indicates where X-ray taken after the surgery X-ray 4 months after surgery

Ulna is cut which allows the ulna has healed and

movement to improve the the AP has fused

way the joint fits together

In cases where the AP has become completely separated from the ulna then it is generally best to remove the process. Sometimes it is considered appropriate to remove the separated AP and also to cut the ulna.

Post-Surgery

After any of the surgeries mentioned above it is important that the patient is rested whilst healing takes place. Exercise is restricted to lead exercise of distances and frequency that does not cause significant worsening of the lameness and such that it can be repeated or slightly increased day by day. In puppies, the recovery period is generally about 2 months following treatment of FCP but nearer 4 months following treatment of UAP.

Physiotherapy / post-operative rehabilitation can be useful in improving the rate of recovery.

What will happen in Later Life if a Dog is affected by Elbow Dysplasia as a Puppy?

If a puppy (or adult) has had elbow dysplasia, whether or not they have shown any clinical signs and irrespective of how they were treated, in later life they might develop signs associated with the secondary arthritis. These might involve stiffness, lameness or poor exercise tolerance. Further information on this problem and its management can be found under “Osteoarthritis”.